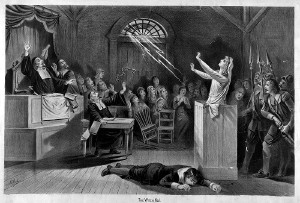

The Crucible

Link for Crucible script PDF:

https://wiki.uiowa.edu/download/attachments/184886812/Crucible%20Script.pdf?api=v2

Fantastic link to an interview about the Salem Witch Hunt:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/the-witches-stacey-schiff-salem_5627aae3e4b0bce34703363e

A frightening account of current-day witch killings.

Can you see yourself in there?

THEY BURN WITCHES HERE

ART BY ALESSANDRA HOGAN

http://highline.huffingtonpost.com/articles/en/they-burn-witches-here/

“The preening of one’s status wasn’t just tabu; it was dangerous. The person who threw many large feasts or cultivated many fruitful gardens ran the risk of making his or her clanspeople jelas, a word that goes beyond mere “jealousy” to convey something akin to “a state of uncontrollable, angry covetousness.” Nowadays, a person can make others jelas by owning a car or running a successful highway-side concession stand. Making others jelas is to be avoided, especially since it is believed that witches are very jelas and vindictive creatures indeed.”

A series of reviews and reactions from the time when the play was first presented in the USA.

A powerful article about our response to female anger

http://time.com/4089074/angry-men-women/?xid=homepage

Why Angry Men Are More Influential Than Angry Women

What is truth?

A seminal article by the BBC about the issue of who to trust and why figuring that out is a big deal.

Lies, propaganda and fake news: A challenge for our age

Wider world example of the way Australia is choosing to handle climate change.

‘Truth vs Lies’ is one of the big issues we face with respect to survival in our day. E.g. Vaccinations, the climate situation. Because these are complicated issues, often the truth includes vital pieces of relevant information from both sides. With accurate weighting and a decent understanding of how the facts fit together in context, a valid, factual truth can be expected to be achieved.

Unfortunately, the internet has created an environment where even the most ludicrous, ignorant and down-right evil people have been given a megaphone. If their concoctions align enough with our fears, suspicions, greed or other biases, we can be easily caught up in their baited hooks. Even the mildest of our elderly aunties can be turned into keyboard warriors when given the right cause to “share” for.

This article does a good job of clearly outlining the murky pathway taken by trouble-making trolls, powerfully motivated, highly financed, biased media and the regular people with opinions who have contributed towards Australia’s particular stance on climate change. A stance that, some could argue, has had life and death consequences, along with deeply embittering the opposing sides – just like the situation in Salem. Fear and the fight for survival drive the action in the play and in our global economies. With so much at stake for all of us, how do we determine the truth? How useful might that truth be if it is not nearly as meme-able or clear as a more “believable” lie?

Something else is out of control in Australia: climate disaster denialism

Myths about the bushfires grow online before finding their way into the rightwing press and the mouths of politicians

An article from the early days of the Trump presidency

The Crucible: the perfect play for our post-truth times

In the 50s, Arthur Miller used 17th-century Salem to comment on the ‘red scare’. His drama is chillingly pertinent in the first weeks of Trump’s presidency

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2017/feb/14/the-crucible-the-perfect-play-for-our-post-truth-times

The play in 10 minutes (Still read the play – because it is brilliant!! And you will be a better human being if you do.)

Spark Notes Summary:

Awesome link to more great info:

Go to this link. http://mrhoyesibwebsite.com

From the homepage, click on Drama then click on The Crucible. This will take you to an excellent resource for quotes, themes, motifs and more.

HOT TIP: Check out KEY QUOTATIONS in preparation for the exam!

PAST EXAM QUESTIONS FOR 3.1

QUESTIONS (Choose ONE)

- “Major characters can find themselves in collision with forces beyond their control, and in many cases their responses to the collision can be described as morally questionable.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “Forget the big players in the world; it is the people in the margins of our society whose stories are most compelling.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “The setting that is most accessible and relevant to the reader is the one that is grounded in realism.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “While the conclusion of a text is important, what really matters is the foundation of a good opening.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “The use of symbolism can transform the most straightforward theme.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “A successful text will be one in which the reader is asked to be more than a spectator, in fact they are encouraged to be involved.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “In order to be informative, the shape and / or style of a text must always be straightforward.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

- “An exceptional text will be one that handles facts and opinion with care.”

To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Respond to this question with close reference to one or more text(s) you have studied.

https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/literature/crucible

THE CRUCIBLE INTRODUCTION

In A Nutshell

The Crucible, by Arthur Miller, is a dramatic re-enactment of the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts in the late 1600’s. Although the play centers on real events, it is not actual “history” – Miller changed the ages of characters and consolidated several historical figures so that there are fewer actors on stage. It was first produced on stage in January 1953. Arthur Miller intended to use the Salem Witch Trials as an allegory about the anti-communist Red Scare and the congressional hearings of Sen. Joseph McCarthy going on in the United States at the time. For more information about the Salem Witch Trials and the McCarthy trials, please see Shmoop History on“Colonial New England” and “Cold War: McCarthyism & Red Scare.”

There is something about the cocktail of fear, anxiety, passion, and jealousy in The Crucible that we find disturbingly familiar. As wild as The Crucible’s plot is, we’ve seen this episode in history over and over again. The Crucible drives home how often history repeats itself.

As we mention in “In a Nutshell”, The Crucible is a parable that tells the tale of a similar “witch hunt” that went down in author Arthur Miller’s time. Fearing the spread of communism and seeing it as a threat to government and individual freedoms, the American government, led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, sought out every single communist in the U.S. They put suspects on trial and forced them to “name names” and rat out their friends and compatriots. Soon the whole country was whipped into a moral frenzy. (Learn more.)

Arthur Miller, playwright extraordinaire, realized that the lingo being thrown around by McCarthy sounded very similar to the language used in the Salem Witch Trials (some 300 years before), a historical period he researched heavily while in college. In comparing the Salem Witch Trials and the McCarthy era, we see a similar cocktail of fear, anxiety, passion, and jealousy pervade the country. Check out Shmoop History’s coverage of “Colonial New England,” and learn more about the parallels between the Salem witch trials and the McCarthy era.

Where would you stand if history were to repeat itself once more and you found yourself in the middle of a “witch hunt?” Would you agree to say something that wasn’t true in order to save your family? What would you do if you became the scapegoat, the person on whom all blame is placed? Arthur Miller helps us try to think about how we would handle ourselves if we were to find ourselves in this situation, and he also makes us think about how emotional humans can get when justice is on the line.

THE CRUCIBLE SUMMARY

How It All Goes Down

Act I of The Crucible opens with Salem’s minister, the Reverend Parris, watching over his sick daughter Betty, wondering what is wrong with her. We soon learn that the entire town is buzzing with rumors that Betty is sick because of witchcraft. Rev. Parris had seen both Betty and his niece Abigail dancing in the forest with his slave, Tituba, the night before. That evening in the forest, he also saw a cauldron and a frog leaping into it. When first questioned, Abigail denies that she or Betty have been involved in witchcraft, but she admits that they were dancing in the forest with Tituba. Abigail lives in the Parris household because her own parents are dead. She used to live at the home of John and Elizabeth Proctor, but they asked her to leave for some mysterious reason.

When another couple, Thomas and Ann Putnam, arrives at the Parris household, they admit that they actually consulted Tituba, hoping she could conjure up the spirits of their seven dead children. They wanted to find out why all seven died so soon after childbirth. To Reverend Parris’s horror, the Putnams emphatically state that his slave Tituba consorts with the dead. The Putnams’s only living daughter, Ruth, is now struck by a similar ailment as Betty Parris, and this obviously has the Putnams up in arms.

When the minister and the Putnams are out of the room, Abigail threatens to harm the three other young girls in the room if they speak a word about what they did in the forest with Tituba.

John Proctor comes to see what is wrong with Betty. He confronts Abigail, who says that Betty is just pretending to be ill or possessed by evil spirits. As Proctor and Abigail have this conversation, it becomes clear that the two of them had an affair while Abigail worked in the Proctor household and Proctor’s wife, Elizabeth, was ill. Abigail tries to flirt with Proctor, but he firmly tells her that their relationship is over. Abigail blames Elizabeth for his behavior, and tells him that they will be together again someday.

Reverend Parris and the Putnams return, and soon, the Reverend Hale arrives at the Parris home. Hale is a famed witch expert from a nearby town. Suddenly, in front of Reverend Hale, Abigail changes her story and begins to suggest that Tituba did indeed call on the Devil. Tituba, surprised at this accusation, vehemently denies it. But when Rev. Hale and Rev. Parris interrogate Tituba, under pressure she confesses to witchcraft, and fingers several other women as “witches” in the village, including Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne. While Tituba and Abigail are accusing women in the town, several other young girls, including Mary Warren (who now works in John Proctor’s household) follow Abigail’s lead and begin accusing other women as well.

Act II opens in the Proctors’ kitchen. Proctor and his wife Elizabeth mourn that their own household helper, Mary Warren, is caught up in the frenzy of accusations. Elizabeth is afraid. They know that Abigail is behind these accusations, and Elizabeth urges Proctor to go to town and reveal that Abigail basically said it was all a hoax. Elizabeth makes an allusion to the affair Proctor had with Abigail, and catches him in a lie – he told her he was not alone with Abigail at the Parris home, but in fact he was. Proctor, irritable and defensive, complains that Elizabeth still doesn’t trust him and never will again, even though he has been a good husband for the last seven months since Abigail left.

Young Mary Warren returns to the Proctors’ house, exhausted from her day assisting in the trials. Proctor reprimands her for being away all day – after all, he declares, Mary is paid to help Elizabeth in the household and has been shirking all of her duties. Mary states that her work in the courts is of great significance; and, with an increased air of importance, Mary insists that she no longer should be ordered around by John Proctor. In a lighter moment, Mary gives Elizabeth a poppet (doll) that she stitched during the day – but, after heightened tension between Mary and Proctor, Mary claims she saved Elizabeth’s life because Elizabeth’s name came up in the trials that day.

When Mary goes to bed, Elizabeth says she has known from the beginning that her name would come up. She tells Proctor that he needs to set things straight with Abigail. He committed adultery with her – and having sex with a woman, Elizabeth says, is tantamount to giving that woman “a promise” – an implicit promise that the two lovers will be together permanently some day. Elizabeth says Proctor must break this promise deliberately. Proctor becomes angry, and again accuses his wife of never forgiving him for his indiscretions.

At this inopportune moment, Reverend Hale arrives. He is going around investigating the people whose names have turned up in the trial. Several other figures from the court show up. They are looking for proof of Elizabeth’s guilt, and inquire about any poppets in the house. Elizabeth says she has no poppets other than the one that Mary gave her that very day. Upon inspection, Mary’s doll is shown to have a needle stuck in its center. As it turns out, earlier that day, Abigail Williams claimed to have been mysteriously stuck with a needle, and accused Elizabeth Proctor of being the culprit. Though Mary does identify the doll as hers, the men cart Elizabeth Proctor off to jail anyway, against the angry protests of Proctor.

Act III opens in the courtroom, where Salem citizens Giles Corey, Francis Nurse, and John Proctor have come to try to interrupt the proceedings. All three have had their wives taken away on accusations of witchcraft. Giles Corey says that some of the accusations have been made so that greedy townspeople can get their hands on the property of those accused. Francis Nurse has brought a signed declaration of the good character of Goody (Mrs.) Corey, Goody Nurse, and Goody Proctor. Ninety-one people have signed it.

In addition, John Proctor brings his household girl, Mary Warren, to confess that she never saw the Devil and she and the other girls have been pretending all this time. When Abigail Williams and the other girls are brought out and confronted with this, they turn on Mary Warren, accusing her of witchcraft. The tension in the courtroom peaks. Proctor tries to put an end to the hysteria by admitting the truth: that he committed adultery with Abigail Williams, who is a liar and an adultress – and this proves that she cannot be trusted.

Abigail denies the accusation of adultery. To uncover the real story, he decides to bring out Proctor’s wife Elizabeth from jail. Since Proctor insists that his wife Elizabeth will not lie, then her confirmation, or denial, of the adultery will set the record straight – and thus affirm Abigail Williams’ credibility, or lack thereof. Before publicly asking Elizabeth about the adultery, Danforth orders both Proctor and Abigail to turn around, so their facial expressions are not visible to Elizabeth. Because Elizabeth does not want to condemn her husband, she lies and says he is not a lecher. Upon this unfortunate turn of events, Danforth proceeds with the hearings, claiming the adultery to be untrue. Danforth sends Elizabeth back to prison as Proctor cries out, “I have confessed it!”

Reverend Hale, shaken, tells Danforth that he believes John Proctor, and asserts that he has always distrusted Abigail Williams. At this, Abigail lets out a “weird, wild, chilling cry” and claims to see a yellow bird on a beam on the ceiling, shrieking that it is Mary Warren threatening her with witchcraft. Eventually, after a creepy scene with the girls following Abigail’s lead of pretend-entrancement, Mary Warren breaks down and joins them once again. Hysterical, Mary lies and says that John Proctor has been after her night and day and made her sign the Devil’s book. Proctor is arrested and taken to jail. Reverend Hale, mortified, denounces the court and walks out.

Act IV opens in a Salem jail cell. It is the day when Rebecca Nurse and John Proctor are to be hanged. Both have resisted confessing up to that point, but Rev. Hale – previously unseen at the court since Proctor’s arrest – is trying to encourage their confession. Even though he knows their confession would be a lie, he wants to save their lives. Rev. Parris is also trying to get them to confess, but that’s because he wants to save his own life: since the trials began, Parris has received some not-so-subtle threats to his life. To make matters worse, Abigail has fled, taking all of Parris’s money with her.

Since Proctor went to jail, over one hundred people have restored their lives by “confessing” to witchcraft, but the town is in shambles. There are orphans, cows wandering all over the place, and people bickering over who gets whose property.

Judge Hathorne and Danforth call upon Elizabeth, still imprisoned, to talk to her husband to see if she can get him to confess. When Elizabeth finally agrees to speak with Proctor (who has been in the dungeon, separated from the other accused), the married couple finally gets a few private moments alone in the courthouse. In these warm exchanges, Elizabeth says she will not judge what Proctor decides to do, and affirms that she believes he is a good man. While Elizabeth will not judge Proctor, she herself cannot confess to witchcraft, as it would be a lie.

Proctor asks for Elizabeth’s forgiveness, and she says he needs to forgive himself. Elizabeth also says she realizes she had been a “cold wife,” which might have driven him to sleep with Abigail. She asks him for forgiveness and says she has never known such goodness in all her life as his. At first, this gives Proctor the determination to live, and he confesses verbally to Danforth and Hathorne.

But Proctor cannot bring himself to sign the “confession.” Knowing that the confession will be pinned to the church door, for his sons and other community members to see, is too much for Proctor to bear. Moreover, he will not incriminate anyone else in the town as a witch. He believes it should be enough to confess verbally and to only incriminate himself. When the court refuses this, Proctor, deeply emotional, tears up the written confession and crumples it. Shocked, Rev. Hale and Rev. Parris plead with Elizabeth to talk sense into her husband, but she realizes that this is, at last, his moment of redemption: “He have his goodness now. God forbid I take it from him!” And so he goes to his death. The curtain falls as we hear the drum beat just before John Proctor is hanged.

Here is the MOST fantastic link to info on important themes in The Crucible.

https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/literature/crucible/themes

Themes include:

Lies and Deceit

Respect and Reputation

Compassion and Forgiveness

Good vs Evil

The Supernatural

Justice

Religion

Jealousy

https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/literature/crucible/themes

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF LIES AND DECEIT

Most of the characters in The Crucible are lying – if not to other people, then to themselves. Abigail lies about her ability to see spirits, as do the other girls; Proctor is deceitful first for cheating on his wife and then for hiding it; and the judge and lieutenant governor and ministers lie to themselves and everybody else in saying that they serve the cause of God’s justice. The twist in the story is that by telling the truth (“I am not a witch”), you die, but you also gain your freedom – that is, you retain your standing with God, and you become a martyr.

Questions About Lies and Deceit

- What are the different methods used by the religious authorities in Salem to decide whether people are telling the truth or not? How would you evaluate the effectiveness of these methods?

- Do any characters deceive themselves? Who and why?

- Why does John Proctor fail to mention that he met alone with Abigail when she told him the accusations of witchcraft weren’t true?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

John Proctor is lying to his wife when he claims that he no longer has feelings for Abigail.

The play makes the radical argument that no kind of deception can ever be ethically justified.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF RESPECT AND REPUTATION

Reputation is extremely important in a town where social standing is tied to one’s ability to follow religious rules. Your good name is the only way you can get other people to do business with you or even get a fair hearing. Of course, reputation meant nothing when a witchcraft accusation was staring you in the face. But it is what made the Reverend Hale begin to doubt whether the accused individuals were actually guilty. Reputation had to do with religion: if you were a good and trustworthy person, you were also a good member of the church. Last but not least, it is for the sake of his reputation and his friends’ reputations that John Proctor refuses to sign a false confession. He would, quite literally, rather die.

Questions About Respect and Reputation

- Why is reputation so important to the people of Salem? What happens if you lose your good reputation (before the witch hunt)?

- In what ways is a person’s good reputation similar to he way we think of it today? In what ways is it different?

- What are some of the factors (lust and greed being two obvious ones) that cause people to ignore the good reputations of their neighbors?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

Although John Proctor goes to his death falsely condemned as a witch, he gains his reputation and respect among those who matter, like his wife, because he refuses to falsely identify his friends and neighbors as witches.

The loss of Abigail’s reputation toward the end of the play shows that characters inThe Crucible eventually earn the reputation they deserve, despite the personal tragedies that might take place along the way.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF COMPASSION AND FORGIVENESS

John Proctor, our main character, is in desperate need of forgiveness at the start of the play, but his wife seems torn about whether to grant it. He had committed adultery earlier that year while she was sick, and though his lover Abigail Williams is now out of his life, she still judges him for it. More importantly, he still judges himself. It isn’t until Elizabeth forgives him, and admits her own fault in the matter, that John Proctor is able to forgive himself and recognize some goodness left in him. It is also what gives him courage to go to his death.

Questions About Compassion and Forgiveness

- Do you think Elizabeth is “cold” for not forgiving her husband, or does she have good reason to suspect that he may not have completely let go of his desires for Abigail?

- What do you think will happen to Rev. Parris after John Proctor is put to his death? The townspeople, furious with the outcome of the trials, have already threatened his life. What will it take for him to be forgiven by the community, or do you think he is beyond redemption?

- Through reading The Crucible, what do you learn about the difference between forgiveness and judgment? Forgiveness and justice? Justice and mercy?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

Even though John Proctor wants his wife’s forgiveness, he actually needs to forgive himself, just like she says.

Although Elizabeth Proctor argues that John is his own worst judge and needs to forgive himself, she is justified to think that he is still not completely faithful in his heart.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF GOOD VS. EVIL

The entire village bases its belief system on the conflict between good vs. evil, or Satan vs. God. Over and over, as people are accused of witchcraft, this paradigm gets dragged out. When Tituba confesses, she claims she wants to be a good Christian now and stop hurting people. She must renounce the Devil. When Mary Warren can’t handle the girls’ accusations, she accuses Proctor of making her sign the Devil’s book and claims she is now with God. The world in The Crucible is clearly divided into these two camps. Unfortunately, everybody’s confused about which side is actually good, and which side is actually evil, though it’s abundantly clear to the reader. It may seem like evil is winning, as one innocent person after another is put to death, but we also see that there is power in martyrdom. The innocent people who confessed are beginning to rebel, and both ministers have recognized their mistakes by the end of the play. Above all, the religion of Salem is incredibly bleak and tends to focus on human frailty and sin to the exclusion of the good things in the world.

Questions About Good vs. Evil

- Are any of the characters in The Crucible beyond redemption? Abigail’s flight at the end furthers the impression that she is simply a bad apple, but even Elizabeth is able to see how Abigail could have interpreted her affair with Proctor as something more than lust.

- The characters in the play are obsessed with evil and the Devil. If the Devil is so powerful, what kind of role, if any, is left to God to perform?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

God has no positive presence for the people of Salem; only Satan is an active force in the world.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF THE SUPERNATURAL

The supernatural is real to the Salem townsfolk. They see evidence of God and evidence of the Devil everywhere. Yet nobody actually sees spirits — though the girls claim they do. The play makes it clear that they are pretending. Their pretense may be a group psychological phenomenon, but in the world as the reader understands it, if there is a Devil, he’s not in Salem: there are only people – some good, some misled, some greedy, some jealous, some vengeful, some evil.

Questions About The Supernatural

- How do random events on earth – the inexplicable death of children, for example – determine the way the supernatural is conceived?

- Do these beliefs about the supernatural change during the course of the play? If not, why not? If yes, how and why?

- Do you think Miller portrays the townspeople as fools for their belief in things like invisible birds that try to attack the soul? In other words, what is Miller’s perspective on the supernatural?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

There are many moments in the play when Miller makes the people of Salem seem more stupid than was necessary for dramatic purposes.

Even though Rev. Hale starts out with a firm understanding of the supernatural, his knowledge is based on books. In Salem, he learns that there is evil, but it is not necessarily manifested in supernatural ways.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF JUSTICE

The Salem of the play is a theocracy, which means that God is supposed to be the ultimate leader, arbiter, and judge. In practice, however, the town’s religious authorities do the governing. God needs men on earth to do his work of justice, and Hathorne, Danforth, Hale, and Parris are all part of that system. They believed that God was speaking through the children to help them prosecute invisible, hidden crimes. The whole system gets turned upside down, and these men of experience and education are completely dependent on the assumption that the children were telling the truth and really did see what they claim to. In Salem during the witch trials, to be accused was to be guilty. To be guilty meant death. And the only way to avoid death was to confess. Though confessing was a way to bring those who strayed back into the fold, in this case it meant a lot of innocent people had to lie in order to keep their lives. Strange sort of justice.

Questions About Justice

- What is the concept of justice, according to the Reverend Paris and Hathorne and Danforth?

- What is Proctor’s concept of justice? How does that differ from other characters, such as Elizabeth’s?

- Does the play take a stand on the question of whether people have an innate sense of justice? For example, do young people and the uneducated fare any better with questions of justice than educated people do?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

Only those characters who have fallen and admit to committing grave errors possess anything close to a sense of justice.

In a play that seems hostile to religion, the ending is especially ironic. John Proctor receives no justice on earth, so the only way that we can think he receives justice would be in some other realm.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF RELIGION

Religion is woven into the everyday life of the Salem of the play. Its exclusive form of Christianity centered on a set of clearly defined rules: you went to church every Sunday, you didn’t work on the Sabbath, you believed the Gospel, you respected the minister’s word like it was God’s, and so on. For people accused of witchcraft, any deviation from these rules in the past can be used as evidence for much greater sins in the present. But ultimately, even good and respected and highly religious women like Rebecca Nurse are accused and put to death, so past respectability and religiosity doesn’t necessarily protect one.

Questions About Religion

- How would you characterize the play’s attitude toward organized religion? Does Miller see all forms of religion as corrupt, or only the particular form embodied by men like Rev. Parris?

- How do the religious beliefs of certain characters help them survive or at least cope with difficult situations?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

Rebecca Nurse is the character in the play who best embodies a positive form of religiosity.

THE CRUCIBLE THEME OF JEALOUSY

Many of the characters are motivated by jealousy and greed in The Crucible. Abigail is motivated by jealousy of Elizabeth Proctor; she wants Elizabeth to die so that she can marry John, Elizabeth’s husband. Thomas Putnam is motivated by jealousy of other people’s property; he wants George Jacobs to die so that he could get his hands on a great piece of land. Little attention is devoted to the subject of envy by any of the characters, even though it is the hidden force driving most of the drama in town.

Questions About Jealousy

- Is it only the obviously “bad” characters in the play, like Abigail and Mr. Putnum, who show jealousy? What about other characters, like John and Elizabeth Proctor?

- How does the theology of Salem prevent its citizens from recognizing envy as a source of the conflict?

Chew on This

Try on an opinion or two, start a debate, or play the devil’s advocate.

Abigail’s actions have no justification other than envy, pure and simple.

Although Abigail is jealous of Elizabeth Proctor, she is not the only source of evil in the play. John Proctor’s deception during his affair with Abigail, when he made a physical “promise” to her, is the source of the play’s conflict.

https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/literature/crucible/characters

JOHN PROCTOR

Character Analysis

Proctor’s Problem

John Proctor, The Crucible‘s protagonist, has some major issues. We can see why. Back in the day, he had everything your average Puritan man could want: a goodly farm to ceaselessly toil upon, three goodly sons to discipline, and a goodly wife with whom to make a home. Proctor was a stand-up guy who spoke his mind. Around town, his name was synonymous with honor and integrity. He took pleasure in exposing hypocrisy and was respected for it. Most importantly, John Proctor respected himself.

Enter: Abigail, the play’s antagonist. This saucy, young housekeeper traipsed in, and, before John knew it, his goodly life was irrevocably corrupted. John made the mistake of committing adultery with her. To make things worse, it was also lechery, as Proctor was in his thirties and Abigail was just seventeen. All it took was one shameful encounter to destroy John’s most prized possession: his self-respect.

When we first meet John Proctor halfway through Act One, we discover a man who has become the thing he hates most in the world: a hypocrite. He is caged by guilt. The emotional weight of the play rests on Proctor’s quest to regain his lost self-image, his lost goodness. Indeed, it is his journey from guilt to redemption, which forms the central spine of The Crucible. John Proctor is a classic Arthur Miller hero – a man who struggles with the incompatibility of his actions with his self-image. (Willy Loman ofDeath of a Salesman, Eddie Carbone of A View From the Bridge, and Joe Keller of All My Sons, all have similar issues.)

Why the Fall?

Adultery? Lechery? John, what got into you? Well, apparently John’s wife Elizabeth was a little frigid (which she even admits), and when tempted by the fiery, young Abigail, John just couldn’t resist. Elizabeth was also sick while Abigail was working for the Proctors, so she probably wasn’t giving her husband much attention. More than likely, though, the cause of John’s transgression is much deeper than base physical reasons.

It’s also quite possible that John Proctor was attracted to Abigail’s subversive personality. Miller seems to hint at this in the first scene in which we see them together in Act One. Abigail tells John that all the hullabaloo about witches isn’t true. She and the other girls were just in the woods having a dance party with Tituba. Miller writes: “PROCTOR, his smile widening: Ah, you’re wicked yet aren’t y’! […] You’ll be clapped in the stocks before you’re twenty” (I.178). The key clue here is the stage direction. It seems to indicate that Proctor is amused and even charmed by Abigail’s naughty antics. This would be in keeping with his personality. We see him challenging authority, from Parris to Danforth, throughout the play.

Man of Action

John Proctor is a passive protagonist; for the first two acts, he does little to affect the main action of the play. (Read more on this in “Character Roles.”) By the time Act Three rolls around, however, he’s all fired up. Spurred by his wife’s arrest, he marches off to stop the spiraling insanity of the witch trials and to hopefully regain his own integrity in the process.

Proctor goes to court armed with three main weapons. There’s Abigail’s admission to him that there was no witchcraft. Also, he has Mary Warren’s testimony that she and the other girls have been faking. Last, but not least, he’s prepared to admit that he and Abigail had an affair. This would stain her now saintly reputation and discredit her in the eyes of the court. Between the wily machinations of Abigail and the bull-headedness of the court, all of these tactics fail. John only ends up publicly staining his good name and getting himself condemned for witchcraft.

Even though John doesn’t achieve his goals of freeing Elizabeth or stopping the overall madness, he does take two significant steps toward regaining self-respect in Act Three. One: he doesn’t stop fighting the false accusations even after he finds out that Elizabeth is pregnant and therefore safe for a while. He feels a greater duty to his community and proceeds anyway. Two: by openly admitting his adulterous lechery, he is no longer a hypocrite. He has publicly embraced his sin.

In Act Four, Proctor conquers the final hurdle on his path to redemption. This is no easy task; he stumbles a bit along the way. In order to save his life, he is tempted into admitting that he is indeed in league with the Devil. He justifies this lie to himself by saying that he’s a bad person anyway. What’s the difference? At least this way, he’ll be alive. Of course, by doing so he’s telling a terrible lie and is also blackening the names of all the other prisoners who’ve refused to give in.

However, when he’s asked to actually sign his name, John refuses. The act of putting his name to paper is just too much. By signing his name he would have signed away his soul. Though he would have saved his life, his goodness would’ve been forever out of his reach. With this final valiant act, John Proctor comes to a kind of peace with himself. He says, “I do think I see some shred of goodness in John Proctor. Not enough to weave a banner with, but white enough to keep it from such dogs” (IV.298).

ABIGAIL WILLIAMS

Character Analysis

Villain Extraordinaire

Abigail is vengeful, selfish, manipulative, and a magnificent liar. This young lady seems to be uniquely gifted at spreading death and destruction wherever she goes. She has an eerie sense of how to manipulate others, to gain control over them. All these things add up to make her a marvelous antagonist.

In Act One her skills at manipulation are on full display. When she’s on the brink of getting busted for dabbling in witchcraft, she skillfully manages to pin the whole thing on Tituba and several of Salem’s other second-class citizens. The horrible thing is that Abigail is the one who persuaded Tituba to go out and cast the spells. Ever since Abigail’s brief affair with John Proctor, she’s been out to get his wife, Elizabeth. Our crafty villain convinced Tituba to put a curse on Elizabeth, hoping to get rid of her and take her place at John’s side.

It’s ironic that the Abigail, who encouraged the witchcraft in the first place, is the one who goes around accusing everybody else. As ringleader, she excites the other girls into a frenzy of emotion, which allows them to condemn as witches the people they know and love. She riles up the entire village’s hatred of witches, just like her 20th-century counterpart, Sen. Joseph McCarthy, riled up Americans’ hatred of communists. Abigail’s main skill seems to be finding people’s flaws, their weaknesses, their prejudices and mercilessly manipulating them to her advantage.

Abigail’s ruthless cunning is shown again in Act Two when she frames Elizabeth Proctor for witchcraft. Later on in Act Three she seems to lose her last shred of humanity by damning John Proctor, whom she claims to love. When John attempts to expose Abigail, she skillfully manages to turn the whole thing around on him, packing him off to the slammer. Abigail rides her power trip out to the end, eventually beating town with all of her uncle’s money. Yes, it seems that Abigail ranks high on the list, along with Iago and maybe Hannibal Lecter, of most skillful antagonists ever.

Redeemable?

The character of Abigail is often accused of being one-dimensional, which is true to a certain extent. She doesn’t express one shred of remorse the entire time, making her seem almost inhumanly diabolical. However, even though Abigail’s actions are ruthless, they are in some ways understandable.

For one, Miller slips in an interesting detail about Abigail’s childhood that gives us a clue as to where her mercilessness might stem from. When she was younger, Abigail watched both of her parents be murdered. She tells the other girls, “I saw Indians smash my dear parents’ head on the pillow next to mine” (I.119). It’s no surprise that a person exposed to such brutality at a young age might eventually act brutally herself.

Abigail’s ruthless, manipulative tactics might also be a result of her low social position. She does have it pretty bad. She’s an orphan. She’s an unmarried teenager. And worst of all for her (in the patriarchal Puritan society), she’s female. The only person lower than her is probably the black slave Tituba. On top of all that, Elizabeth Proctor has been going around dropping hints that Abigail is sleazy, lowering Abby’s social status even more. With all this in mind, it’s pretty understandable that Abigail might seize any chance to gain power.

Historical Abigail

Abigail Williams was a real person, and she did spearhead the group of girls that saw spirits and pointed out the witches in Salem’s midst. The historical version was a bit different than the fictional character, though. Arthur Miller explained that one discovery he made while digging into the actual history of the Salem Witch Trials set his imagination on fire: Abigail Williams, the mover and shaker of the witch-finding craze, had been the Proctors’ house servant for a short time. Though Abigail called Elizabeth a witch, “with uncharacteristic fastidiousness she was refusing to include John Proctor, Elizabeth’s husband, in her accusations despite the urgings of the prosecutors” (source).

While there is no actual evidence that the real John Proctor and the real Abigail Williams had an affair, Miller could find no good reason why Abigail distinguished so vehemently between the guilt of a husband and wife. Arthur Miller took creative license with her character to make the connection between sexuality and politics more dramatic. In reality though, Abigail Williams was only eleven years old at the time of the witch trials. We will always wonder why she accused Elizabeth and not John. Maybe he was just nice to her. Who knows?

ELIZABETH PROCTOR

Character Analysis

Elizabeth’s positive qualities are also her negative ones. She is a virtuous woman who is steadfast and true. These traits also make her a bit of a cold fish. When we first meet her, she’s especially cold and fishy. She’s got good reason to be, though, because her husband has recently had an affair with their housekeeper, Abigail Williams.

Elizabeth’s reaction to the affair reveals a bit of a vindictive streak. When she discovered her husband’s sin, she gave Abby the boot and then proceeded to drop a few hints around town that the girl may just be tainted. (Isn’t John a little responsible, too?)

For the most part, though, Elizabeth is a stand-up woman. Throughout the play, she seems to be struggling to forgive her husband and let go of her anger. And, of course, her hatred of Abigail is understandable. Elizabeth’s dislike of Abigail seems justified later on in the play when Abigail tries to murder Elizabeth by framing her for witchcraft.

Overall, Elizabeth is a blameless victim. The only sin we see her commit is when she lies in court, saying that John and Abigail’s affair never happened. This is supposedly the only time she’s ever lied in her life. Unfortunately, it’s really bad timing. Though she lies in an attempt to protect her husband, it actually ends up damning him.

After she’s spent a few months alone in prison, Elizabeth comes to her own realization: she was a cold wife, and it was because she didn’t love herself that she was unable to receive her husband’s love. She comes to believe that it is her coldness that led to his affair with Abigail. This realization helps Elizabeth forgive her husband, and relinquishing her anger seems to bring her a measure of personal peace. Elizabeth’s noblest act comes in the end when she helps the tortured John Proctor forgive himself just before his death.

REVEREND PARRIS

Character Analysis

Parris is a wormy little character. Miller says in his notes that he found nothing redeemable about the historical Parris. As a result, he evidently felt no need to make his fictional version any better. First of all Parris is greedy. John Proctor accuses Parris of this several times in the play. The Reverend gives weak justifications, but never denies any of the accusations. Some examples of Parris’s greed include: quibbling over firewood, insisting on gratuitous golden candlesticks for the church, demanding (against time-honored tradition) that he have the deed to the house he lives in.

Parris’s repeated demonstrations of exceedingly selfish behavior don’t help his case. In the very first scene, we see him standing over his daughter Betty’s sick bed. At first the audience might feel bad for him. But then they’d quickly realize that Parris is just worried about his reputation. He’s afraid that if people think there’s witchcraft in his household, he’ll lose his position as minister of Salem. In Act Three, when he shows his spineless selfishness once again when he perjures (intentionally lies in court) himself. He tells the court that he saw no naked dancing in the woods, yet we know that he did, because he says as much to Abigail.

Parris’s lack of redeemable qualities becomes even more apparent in Act Four. At first it seems like he may have come to his senses, because he’s asking Danforth to postpone the hangings. Abigail has flown the coop, making it pretty darn obvious she was lying the whole time. It turns out that Parris isn’t pleading out of remorse at all, though, he’s only concerned for his own life. He found a dagger in his front door, and is afraid that if respectable citizens like John Proctor and Rebecca Nurse are hanged, the town will revolt. Most despicably we see Parris cry – not because of all the people who he’s helped to senselessly murder, but because Abigail stole his money and he’s now broke. Yes, by the end of the play, Reverend Parris is thoroughly exposed as the sniveling parasite that he is.

MARY WARREN

Character Analysis

Mary is a likeable enough character, but ultimately proves herself to be a bit spineless. She’s one of the girls who was caught in the forest with Abigail, dancing and conjuring spirits – though we quickly learn that she just watched and did not participate. She becomes part of the court that condemns witches. At first she seems to enjoy the power it gives her. When clearly innocent people begin to be convicted, however, Mary feels bad about the whole thing.

The first sign we see of Mary’s guilty conscience is when she makes a poppet (a doll) for Elizabeth Proctor, who she currently keeps house for. Abigail has brought Elizabeth’s name up in court, and Mary knows that Abigail did it only for vengeance. Mary was there when Abigail got Tituba to put a curse on Elizabeth, and she also knows about Abigail’s affair with John Proctor.

Mary’s feeble attempt at recompense backfires terribly, however, as Abigail uses the poppet to frame Elizabeth for witchcraft. This, of course, makes Mary feel even worse and she agrees to go with John Proctor and testify against Abigail in court. Mary’s ultimately spineless nature is revealed in the court scene, when under pressure of being hanged she once again flips, accusing John Proctor of witchcraft and Devil worship.

While Mary causes a lot of harm in the play, she lacks Abigail’s maliciousness. She’s just a weak girl who gets in way over her head. Yes, Miller’s portrait of Mary is sympathetic, but doesn’t let her off the hook. It could be that he’s pointing out how even good hearted people can commit destructive acts when swept up in mass hysteria like the Witch Trials (or McCarthyism and the Red Scare).

REVEREND JOHN HALE

Character Analysis

With notable exception of John Proctor, Hale gets our vote for most complex character in The Crucible. We say so, because Hale goes through a major personal journey over the course of the play. He starts off with really good intentions. In Act One, Miller writes of Hale: “His goal is light, goodness, and its preservation.” This guy has trained and trained to be the best witch-hunter ever, and he’s psyched to finally get a chance to show off his stuff. Though he’s probably a little full of himself, but ultimately his goal is to valiantly fight the Devil. What could be wrong with that? Well, a whole lot.

In Act Two, we see that Hale’s former confidence is slowly eroding. This is demonstrated by the fact that he shows up at the Proctors’ house of his own accord. He’s there without the court’s knowledge, trying to get an idea of who the Proctors are for himself. This independent action is a big hint that he’s probably beginning to doubt the validity of his own conclusions. When John Proctor gets convicted in Act Three, through Abigail’s transparent machinations, Hale’s confidence is shattered. He quits the court and storms out in anger.

The transition from overconfidence to total disillusionment is already a big journey, but then Miller takes his character a step further in Act Four. After taking off for some soul searching, Hale turns up hoping to save some lives. He councils convicted witches to confess, so that they won’t be hanged. Hale is knowingly counseling people to lie. He’s lost all faith in the law, and there’s a good chance his faith in God is a bit shaky as well.

Hale’s last effort to wash some of the blood of his hands fails. He’s not able to convince anyone to confess. When John Proctor marches off to his martyr’s death, Hale pleads with Elizabeth to change her husband’s mind, screaming, “What profit him to bleed? Shall the dust praise him? Shall the worms declare his truth?” (IV.207) Words like these show that Hale has become a completely different man than the one we met at the beginning of the play. The tortured reverend is a great example of the kind of rich, morally ambiguous character for which Miller is famous.

TITUBA

Character Analysis

Tituba, the Reverend Parris’s slave, is a woman from Barbados who practices what the Puritans view as “black magic.” Of course, it’s mainly because the conniving Abigail manipulates her into doing it. Tituba admits her supposed sin, but we never really find out what happens to her. The ambiguity of her fate actually emphasizes that whether or not these women are in fact witches is beside the point.

And we have to say, although there is nothing in the play that directly comments on it, racism undoubtedly plays a large part in her fate. The fact that she was convicted at all for her practices is actually inherently prejudice. Before being brought to Massachusetts, Tituba never saw her singing, dancing, and spell casting as evil. Such practices were spiritual and descended from her African roots. This is shown in Act Four, when we see poor Tituba say to her jailer:

Devil, him be pleasure-man in Barbados, him be singin and dancing […] It’s you folks – you riles him up ’round here […] He freeze his soul in Massachusetts, but in Barbados he just as sweet. (IV.15)

It’s ironic that the Puritans, who came to America to escape religious persecution, would practice such deliberate, cruel, and ignorant persecution themselves.

GILES COREY

Character Analysis

Giles Corey is a strong old man and has only recently converted to Christianity. He’s likeable, but is not too bright. His biggest bumble in the play is when brings up the fact that his wife reads strange books. To Giles, any book is strange and the idea of a woman wanting to read totally blows his mind. His mention of this fact leads to an accusation that his wife is a witch.

Giles feels terrible about this. He knows his wife is innocent and recognizes that his own actions have led to her incarceration and impending death. He attempts to defend his wife by going to the court and showing them proof that, in at least one case, the accusation is based on Thomas Putnam’s greed for a neighbor’s bit of land. This backfires and he is condemned himself.

Corey’s incredible strength of character is shown in the end when he neither confesses to, nor denies, the charges of witchcraft. By doing so, he ensures that his sons can legally inherit his property. Even though he is brutally tortured by having crushingly heavy stones place on his chest, the only thing Giles he says is “More weight” (IV.186).

Miller would go on to pull a “Giles Corey” of his own, when he was called to testify before McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Despite tremendous pressure, Miller refused to name names of suspected Communists.

DEPUTY GOVERNOR DANFORTH

Character Analysis

Deputy Governor Danforth oversees the witchcraft trials in Salem, as in other parts of Massachusetts. He likes to think of himself as fair-minded, so it disturbs and angers him to discover that people fear the court. He believes that no innocent person should fear the court, and that he and Judge Hathorne are guided by God, so nobody will be punished unjustly. As a result, he fails to examine evidence critically or to act when he could to stop the hysteria. Even at the end, when it’s obvious that the society is disintegrating, he refuses to see the role that the witchcraft trials and hangings have played in it.

Miller’s depiction of the characters of the people who prosecuted witches, like Danforth, was sometimes criticized as being too excessive. Miller agreed, but defended his depiction as adhering to the facts of history. Miller suggested Danforth was important because he helped define and defend the boundaries of society, the rules that people lived by. His character, Miller says, is driven by the idea that mankind must be protected from knowledge, an idea that Miller characterized as believing that “evil is good.”

THOMAS PUTNAM

Character Analysis

Thomas Putnam is a greedy man who urges Reverend Parris to be strong and face up to the witchcraft in their midst. He uses his daughter to accuse people whose property he covets. Miller, and most historians, believed that many of the accusations of witchcraft were based in these sorts greedy, selfish desires. Perhaps, Miller intended audiences to see parallels between Putnam and individuals in Miller’s own time who were accusing people of being communist for equally selfish and petty reasons (learn more in “Cold War: McCarthyism & Red Scare“).

MRS. ANN PUTNAM

Character Analysis

To be fair, Mrs. Putnam might not mean any harm – she just wants to find out why her babies have been dying, and she’s sad and angry about it.

REBECCA NURSE

Character Analysis

Rebecca is a pillar of the community, a devoutly religious woman in her seventies. When she is accused of witchcraft, it makes the Reverend Hale pause and reconsider whether the proceedings are just and fair. After her arrest and conviction, Rebecca continues to be a pillar of the community, but this time, the community of falsely accused people. She is an example of strength and resolve for those who choose not to confess, even though it means going to their death.

FRANCIS NURSE

Character Analysis

Francis Nurse is a good man and a good husband who has the courage to stand up to the court and say that the judge and governor have been deceived.

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

Though there isn’t a lot of symbolism in the story, the events in the play itself are an allegory for the intolerance of McCarthyism. For a decade spanning the late 1940s to the late 1950s, the American government was intensely suspicious of the possible influence of communism on citizens and institutions. The FBI accused thousands of people of “un-American activities” and monitored many more; these people’s careers and personal lives were frequently destroyed. More often than not, there was little to no evidence to support the accusations. Nevertheless, the FBI and various government groups involved in monitoring or accusing individuals, such as The House Un-American Activities Committee, enjoyed widespread support from the American population. (Learn more here.)

Similarly, in The Crucible, there is little evidence that much witchcraft activity is going on, but once accusations started flying, many innocent people get caught in the web of hysteria. Lives are destroyed and people die based on zero evidence.

https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/literature/crucible/analysis

ANALYSIS: SETTING

Where It All Goes Down

Salem, Massachusetts, 1692.

In 1692, Salem was populated by Puritans who believed in black-and-white lines between good and evil. The powers of darkness were real forces to them, which could wreak havoc and destruction on society if unleashed. The system of government was a “theocracy,” which meant that God was the true leader of society, and he expressed his will through the actions of men and women. In the Old Testament, we hear stories of how God led directly through Moses; Salem, likewise, was led through men who were supposed to be directly connected to God.

In theory, if you believe in a loving God, this should work; but in practice, men lust after power regardless of their principles. This meant that God’s power was mediated through men, and men made the rules. Among those rules were strict guidelines for what it meant to be a Christian, and what it meant to follow God. Miller describes the forest as the last bastion of evil according to Puritan understanding, so the forest where Abigail and the girls danced was seen as ruled by the Devil – while the town of Salem was ruled by God. The entire play is about the moral contradictions inherent in Salem at this time, and how its strict religious theology became twisted and led to the death of innocent people.

ANALYSIS: NARRATOR POINT OF VIEW

Who is the narrator, can she or he read minds, and, more importantly, can we trust her or him?

Third person omniscient

The narrator actually inserts himself into the play several times to describe characters and tell us what we should think about them, such as when he tells us that Judge Hathorne is a bitter man. In addition, each inserted stage direction indicates exactly what a character is thinking or feeling. The narrator is able to jump into any character’s mind at any given moment.

ANALYSIS: GENRE

Drama

The Crucible is a four-act dramatic play, produced on Broadway and later made into a film. It uses pure dialogue to convey the tension, resolution, and themes, with a few directions for action. It was intended to be performed rather than read. Though most people nowadays experience the play on the page, it really works best as a stage production.

ANALYSIS: TONE

Take a story’s temperature by studying its tone. Is it hopeful? Cynical? Snarky? Playful?

Critical

The tone Miller adopts towards the subject of witch trials and witch-hunts, and towards the characters that perpetuate them, is unequivocally critical. He is sympathetic towards individual characters who are the victims, such as the Proctors or Rebecca Nurse.

ANALYSIS: WRITING STYLE

Simple, old-fashioned

The dialogue is the simple language of country folks, while at the same time employing old-fashioned vocabulary and grammar. The narrative asides are slightly more complex and use regular, standard, 1950s everyday language.

ANALYSIS: WHAT’S UP WITH THE TITLE?

Nowhere in this play is there of a mention of the word “crucible.” So where exactly did that come from. And what in the world is a crucible anyway?

It turns out the word has two definitions.

Humans Were Harmed in the Course of These Laboratory Tests

Let’s tackle the first definition, shall we? A crucible is a piece of laboratory equipment used to heat chemical compounds to very high temperatures or to melt metal. It’s a little container full of violent reactions. Seems like a pretty good metaphor for the violent hysteria that the little village of Salem contained during the witch trials. With all those folks jammed together in a tiny town, there are bound to be some hot tempers.

Yep, Salem became a crucible for many people living there, when they were brought before the religious court and accused falsely of being witches. If an accused person did not confess, she was hanged. If she did confess, she was spared death but marked for life as a person who worshipped the Devil. Classic catch-22. Under such conditions, several characters in this play, especially the central characters, John and Elizabeth Proctor, are forced to face their own internal demons, a process that ultimately leads to internal, spiritual transformation.

Trial by Fire

The term crucible can also be used metaphorically, which brings us to our next definition: a test or a trial. Folks use the term crucible to refer to a difficult test. And there sure are a lot of tests going on in The Crucible. There are the tests to determine who’s a witch. Then there are, quite literally, the trials the accused must undergo. And then, as we mentioned above, there are the more internal trials, where folks’ deepest, most powerful beliefs are put to the test by their less than ideal circumstances.

20th Century Salem

The title (and the entire play) is also a metaphor for the anti-communist craze of America’s Red Scare, led by Sen. Joe McCarthy. Thanks to the efforts of McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee, the whole United States became a “crucible,” in which citizens beliefs about what it means to be American were deeply tested, in the highest halls of government.

ANALYSIS: WHAT’S UP WITH THE ENDING?

The Crucible ends with John Proctor marching off to a martyr’s death. By refusing to lie and confess to witchcraft, he sacrifices his life in the name of truth. At the end of the play, Proctor has in some way regained his goodness. Check out John’s “Character Analysis” and “Character Roles” for more on his dramatic transformation.

Much is said elsewhere in this guide about John Proctor’s journey, which is completed by his execution. As such, we’d like to use this section to focus on the actual last two lines of the play. We think it’s interesting that, though this is Proctor’s story, Miller doesn’t give him the last word. Instead Reverend Hale and Elizabeth Proctor get the honor. Miller writes:

HALE: Woman, plead with him! […] Woman! It is pride, it is vanity. […] Be his helper! What profit him to bleed? Shall the dust praise him? Shall the worms declare his truth? Go to him, take his shame away!

ELIZABETH: […] He have his goodness now. God forbid I take it from him! (IV.207-IV.208)

It seems to us that these last two lines raise an interesting philosophical question, to which there is no right answer. Hale does have a pretty good point. Though the character of Proctor is often lauded for his integrity, is he helping his family by dying? His wife, sons, and unborn child will have to make it in the world without him. This is none too easy in the harsh Massachusetts wilderness. His choice of death could also be viewed as a form of suicide, which is unacceptable to many Christians. His death might also be interpreted as inherently selfish, because he’s placing his own self-image over the good of his family.

Of course, we doubt that Proctor’s wife, Elizabeth views it as abandonment. Though, she tries her best to remain neutral when John is trying to decide whether or not to confess, it seems pretty obvious in the subtext that she thinks he should die an honorable death. It makes total sense to a Puritan. They believed, as most modern Christians do, that a person’s time on Earth is a mere speck when compared to one’s afterlife. She likely believes that if John lies, he’ll go to hell for all eternity. If he dies a martyr’s death, he’ll inevitably see his family again and spend all eternity with them in heaven.

It looks like both Hale and Elizabeth have a point. There are pros and cons no matter what decision Proctor makes. Miller’s choice of these particular last two lines seems to almost ask the audience a direct question. Which is more important: your honor or your life? There’s no definitive answer to this question. It’s totally subjective. Like every great play, The Crucible gives its audiences a lot to think about long after they’ve left the theater.

ANALYSIS: PLOT ANALYSIS

Most good stories start with a fundamental list of ingredients: the initial situation, conflict, complication, climax, suspense, denouement, and conclusion. Great writers sometimes shake up the recipe and add some spice.

Initial Situation

Betty Parris is sick with an illness that seems to be “unnatural”. People are suggesting that it might be witchcraft.

The play opens in Betty Parris’s bedroom. Her father, the Reverend Parris, is wondering what is wrong with her. He soon learns that all over town, there are rumors that she’s been bewitched. He doesn’t want to believe it, but the night before, he did catch his niece Abigail, his daughter Betty, and some other town girls dancing in the forest. That’s bad enough, but he thinks he might have seen a dress on the ground, which means naked dancing, and he knows he saw a cauldron. But for now, he’s not mentioning these things to anybody as he figures out what to do. He’s worried that if there is witchcraft in his house, his career and personal wealth will be ruined.

Conflict

Tituba confesses to witchcraft and reveals the names of many other women in Salem who are also consorting with the Devil. The girls, led by Abigail, begin to accuse other women of witchcraft.

Before Tituba is brought to Betty’s room to be questioned, Abigail threatens the other girls not to breathe a word of the truth, other than what she has already revealed, and we learn that Abigail is a treacherous person. She tells Proctor that Betty is not really sick; she just got frightened when her father found them the night before. Abigail lets Proctor in on the secret, then confronts him and asks him to reveal his love for her. He denies her, and says she should forget him. But we realize that Proctor is in for a bumpy ride, given Abigail’s deceptive actions so far. When Hale confronts Abigail about the witchcraft, she blames Tituba. Faced with the power of the minister and the threat of death if she doesn’t confess, Tituba confesses everything and also claims she’s seen other women in town with the Devil. Then the girls begin to claim that they, too, saw these women with the Devil.

Complication

Elizabeth Proctor is arrested.

As the witch hysteria moves through the village, more and more women are arrested as witches. Their trials are swift and speedy and almost all are convicted. If they confess, however, they are released. Soon, however, the girls stop pointing the finger at the town’s less reputable citizens and begin accusing the religious and respectable Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey. Elizabeth warns her husband to put a stop to it by telling the court what he heard Abigail say. But she’s too late. When Abigail sees her chance to accuse Elizabeth, she takes it. After observing Mary Warren make a doll (poppet) and stick a needle in it during one of the trials, she later claims that somebody stuck a needle in her. She says it is Elizabeth Proctor’s spirit that has done it, and proof will be found in the poppet in her house. Indeed, the poppet is found and Elizabeth is arrested.

Climax

John Proctor tries to get his wife released from jail by appealing to the court. His confessions of adultery with Abigail, and the failed testimony of Mary Warren, bring things to the boiling point.

Proctor brings Mary Warren to court, where she confesses that she was lying and never saw spirits. Unfortunately, she can’t reproduce her fake hysteria without the other girls doing it, too. Abigail and the other girls begin to pretend that Mary Warren herself is bewitching them, even as they all stand there. All seems lost until Proctor confesses that Abigail is a whore, that he committed adultery with her. Abigail denies it, but Danforth calls Elizabeth Proctor out to ask her if her husband is a lecher. Proctor has assured Danforth that his wife never lies, but in this case, she does, in order to protect his name. Danforth sends her away. Mary Warren seizes the opportunity to redeem herself and rejoin her social group by suddenly accusing Proctor of making her sign her name in Satan’s book. She joins the girls again, confessing that she is now with God again. John Proctor is arrested as a witch.

Suspense

Elizabeth and John discuss whether he should confess – and thus save his life – on the day he is scheduled to hang in the gallows.

Just before his death, the ministers and officials of the court allow Elizabeth Proctor to speak to her husband. They hope she can convince him to confess, to save himself from death. Instead, Elizabeth lets him know that she forgives him for his indiscretions with Abigail, and that she shares in the blame. She feels he is taking her sin upon himself. Proctor decides he wants to live and agrees to confess. Reverend Parris praises God.

Denouement

John Proctor decides not to confess.

When Proctor realizes that in order to confess, he not only has to sign his name to a written document, but he must also denounce his friends as witches, he can’t do it. It is one thing to lie about himself, but it is another thing to ruin his friends’ reputations. Instead of a false confession, he decides to go to the gallows.

Conclusion

John Proctor goes to his death, redeemed as a good man.

When Proctor decides to tear up the confession, he saves his soul. Until that moment, he has decided to confess in part to save his life but in part because he doesn’t feel like he deserves to die in this manner, as a martyr and a saint. But when he chooses death, he recognizes his fundamental goodness as a man.

ANALYSIS: BOOKER’S SEVEN BASIC PLOTS ANALYSIS

Christopher Booker is a scholar who wrote that every story falls into one of seven basic plot structures: Overcoming the Monster, Rags to Riches, the Quest, Voyage and Return, Comedy, Tragedy, and Rebirth. Shmoop explores which of these structures fits this story like Cinderella’s slipper.

Plot Type : Rebirth

Falling Stage

John Proctor discusses Abigail’s mischief with her.

Because John Proctor has committed adultery with Abigail Williams, he is still under her sway. When Proctor visits to find out why Betty is sick, and to mention how the entire town seems to think it’s witchcraft, Abigail admits to him that she, Betty, and the other girls were just playing games. We know, however, that she was drinking a potion to make Elizabeth Proctor die so she could become Proctor’s next wife. Although Proctor doesn’t know it, we the audience are aware that Abigail is a dangerous personality and that Proctor is vulnerable.

Recession Stage

John and Elizabeth Proctor are relatively isolated from the frenzy that is eating the town alive. They only hear about it through rumor and their housemaid, Mary.

John and Elizabeth discuss farm issues, and it’s clear that their relationship is still strained. John wants forgiveness, and Elizabeth wants to give it to him, but the hurt is deep.

Imprisonment Stage

Elizabeth is arrested as a witch, and John Proctor tries in vain to save her and clear her name. In so doing, Proctor himself is arrested and accused of being a witch as well.

The Proctors’ housemaid Mary returns home and gives Elizabeth a poppet with a pin stuck in it. Mary explains how she saved Elizabeth’s life, and Elizabeth urges Proctor to go to the court and explain what he knows about Abigail. But it is too late. Cheever and Herrick arrive to arrest Elizabeth. The poppet is considered proof that she’s a witch: earlier that evening, Abigail was eating and was suddenly stuck by a pin in her thigh. She said Elizabeth Proctor was the one who tried to hurt her, and if they looked on the property, they’d find a poppet with a pin in it. They do, and Elizabeth is led away.

Later, in the courtroom, John Proctor tries to save his wife by exposing Abigail Williams as a fraud and a whore. To ascertain the truth, Deputy Governor Danforth asks the imprisoned Elizabeth Proctor if her husband is a lecher. To save his name, she lies for the first time, and claims he is not a lecher. Unfortunately, Proctor has already confessed, so Elizabeth’s untruthfulness actually undermined him rather than helped him. Soon after this event, Proctor himself is accused of being a witch and ends up in prison.

Nightmare Stage

The day of John Proctor’s hanging – and his dilemma about whether to confess.

Proctor wrestles with his soul in prison, feeling that he doesn’t deserve to go to the gallows branded as a martyr and a saint. He discusses how he is feeling with his wife, and she lets him know that she realizes that it was her coldness that led him to seek Abigail. She feels he is taking her sin upon his shoulders and suggests that he stop judging himself. The shock of this confession rips Proctor right out of his self-pity, to look at the world with new eyes. He wants to live, he decides, and so he will confess.

Rebirth Stage

John Proctor tears up his signed confession and walks to the gallows.

Even as he confesses to a sin he didn’t commit, Proctor realizes that he can’t tell lies about the sins of other people. It is one thing to lie about himself and to take the rap to his reputation. But it is yet another thing to smear his friends’ good names. When Proctor decides to tear up the confession, he redeems himself and recognizes that he’s a good man. When he chooses death, he recognizes his fundamental goodness as a man. He is reborn.

ANALYSIS: THREE ACT PLOT ANALYSIS

For a three-act plot analysis, put on your screenwriter’s hat. Moviemakers know the formula well: at the end of Act One, the main character is drawn in completely to a conflict. During Act Two, she is farthest away from her goals. At the end of Act Three, the story is resolved.

Act I

John Proctor learns that Abigail Williams is lying and fabricating stories of witchcraft throughout Salem.

Act II

After John Proctor tries to save his wife from the witchcraft charges in court, Proctor is arrested and incarcerated on charges of witchcraft, with the threat of death if he does not confess.

Act III

John Proctor chooses not to confess to witchcraft and is spiritually redeemed and reconciled with his wife; he goes like a hero to his death, with his goodness and integrity intact.

ANALYSIS: TRIVIA

Brain Snacks: Tasty Tidbits of Knowledge

Although the tale of Abigail Williams’s jealous desire to possess John Proctor is interesting, and the stuff of soap operas, it has no basis in historical fact. The truth is that historians are still trying to come up with explanations for why an entire community of devout believers (who were not normally violent) might have become bloodthirsty moralizers, intent on sniffing out the evil in their midst. Here are a few historical inaccuracies, according to Margo Burns: Betty Parris’s mother was still alive; there is no hard evidence that Abigail Williams was Parris’s niece, though she may have been a relative; there never was any wild dancing in the woods, and the Rev. Parris never caught the girls dancing in the woods; in 1692, the Putnams had six children, and they were all alive. You can read the full list of inaccuracies here.

ANALYSIS: STEAMINESS RATING

Exactly how steamy is this story?

PG

We don’t actually see any nakedness or sex in The Crucible, but we do learn that Abigail Williams and the rest of the girls liked to dance naked in the woods while they contacted departed spirits.

John Proctor lusted after Abigail Williams while his wife was sick and they had passionate sex in the barn (which Proctor indicates was the appropriate place for that kind of activity). Though he does not seem too ashamed of his actions, Proctor accuses Abigail of being a whore, and his wife claims she is a harlot. Later, however, Elizabeth Proctor admits that perhaps her own cold nature drove her husband to adultery. Regardless, the only real sex occurs off-stage, in a barn eight months before the story starts.

ANALYSIS: ALLUSIONS

When authors refer to other great works, people, and events, it’s usually not accidental. Put on your super-sleuth hat and figure out why.

Historical References

The Crucible is peopled with historical figures – Deputy Governor Danforth, John and Elizabeth Proctor, the Reverends Parris and Hale, Abigail Williams, Rebecca Nurse, etc. – but Arthur Miller took liberty to create a fictional story based on historical events. We don’t know, for example, why in real life Abigail Williams accused Elizabeth but not John Proctor. Miller has used his imagination to explain one possibility, but in doing so he had to change certain facts – such as raising Abigail’s age from 11 to 17 years old. While the names refer to real historical people, it’s also important to remember that The Crucible itself is fiction.

THE CRUCIBLE QUESTIONS

Bring on the tough stuff – there’s not just one right answer.

- The Crucible has a hard-hitting “moral of the story.” What is it? Do you think this moral is still applicable in today’s world?

- What sort of modern-day witch hunts are you aware of? How are they similar to the Salem witch hunts? How are they different? Why do you think humans are so prone to go on witch-hunts?

- You already know that Miller had the anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee in mind when he wrote about the witch trials. In what ways was McCarthyism similar to the witch trials of Salem and in what ways was it different?

- Can you imagine a witch trial (and witch-hunt) like this in today’s world, in the U.S.? Why or why not? What has changed to make such an event impossible or what has remained the same to make it possible?

All credit for this previous section of the material goes to schmoop.com

Author: Margo Burns

Name of Page: Arthur Miller’s The Crucible: Fact & Fiction (or Picky, Picky, Picky…)

Name of institution/organization publishing the site: This site has no institutional affiliation, although you may want to include the name of the entire website,17th Century Colonial New England, depending on the format you use.

Date of Posting/Revision: Sep. 25, 2018

Website address: http://www.17thc.us/docs/fact-fiction.shtml

Date Retrieved/Viewed: Jan. 6, 2020

Arthur Miller’s The Crucible:Fact & Fiction

(or Picky, Picky, Picky…) by Margo Burns Revised: 10/18/12